Going on Assignment in Prague July 2022 – July 9, 2022

A Sporting Chance

By Melanie Ritchot

A soccer team for Roma kids in the Czech town of Neratovice has boosted school attendance and given the players a wider field of play.

by Melanie Ritchot

Making it onto Neratovice’s soccer team for Roma youth is simultaneously easy and difficult. Students can play on just three conditions: that they keep their grades up, stay in school, and do their household chores. Despite facing racism and low educational levels – common challenges for the Czech Republic’s Roma population – these kids are beating the odds, according to their coach, 35-year-old Martin Demeter.

“I want to show them that Roma kids can aim for higher things,” he says.

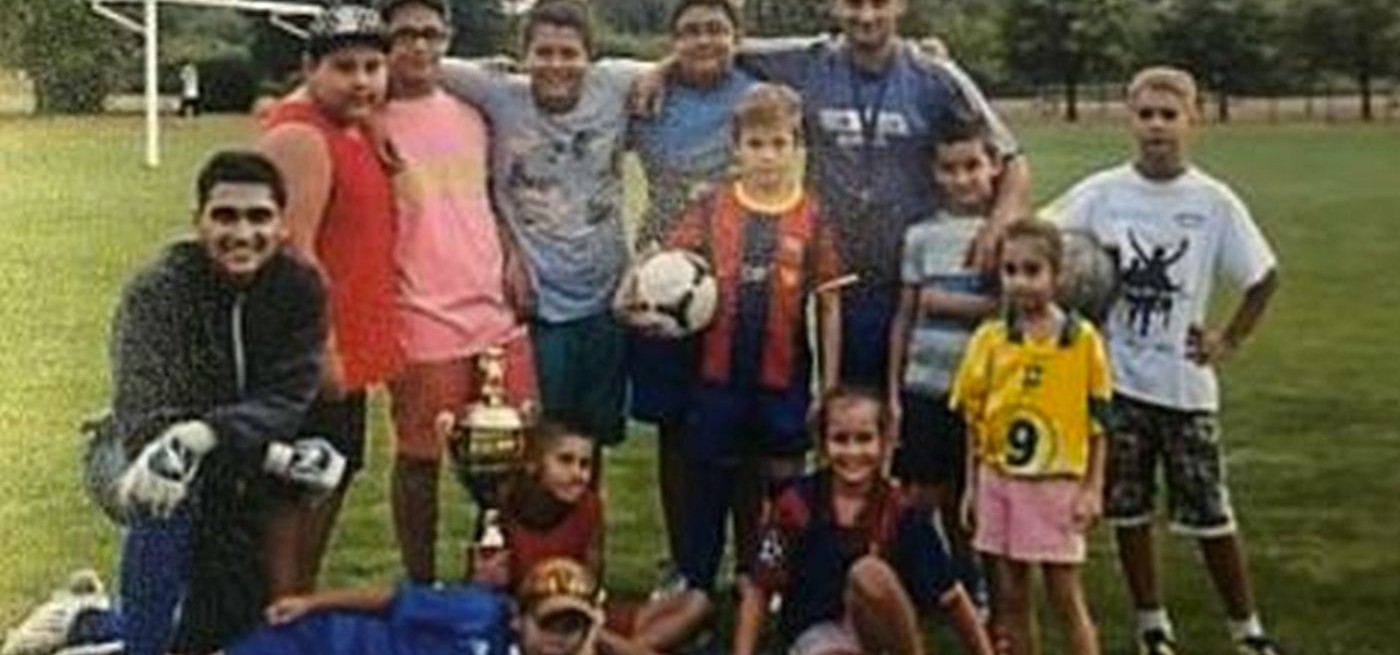

For the last five years, Demeter (pictured), himself a member of the Roma community, has been coaching a small group of Roma students in Neratovice – a town of 16,400 inhabitants, close to Prague – and sees their education, life choices, and community as being just as crucial as the sport.

For the last five years, Demeter (pictured), himself a member of the Roma community, has been coaching a small group of Roma students in Neratovice – a town of 16,400 inhabitants, close to Prague – and sees their education, life choices, and community as being just as crucial as the sport.

“It’s not important how big the program is, but what result it has,” says Lucie Pleskova, manager of the Education and Youth Program at the Open Society Fund Prague, which has been providing assistance to Roma since the 1990s. “Every child who has a better education and a chance for a better life counts.”

New Motivations

Before the soccer program was implemented, barely any of the players attended school, according to Demeter. “Now they all want to go so they can play.”

Encouragingly, after playing for SK Roma Neratovice, one student wants to be a police officer and another is applying to university.

This increased level of achievement and ambition is in stark contrast to the national situation of Roma children in the Czech Republic, who are less likely than any other group to complete secondary education. According to a recent EU report, 72 percent of Roma students leave school early.

“[The program] motivates children to study and to have responsibility for their duties, which is crucial for their future,” says Pleskova.

Demeter feels he is an important role model for the young soccer players, and wants to help raise them to be responsible. The way he went about starting the team underlines this approach. In the early stages, Demeter went door-to-door, to schools and homes, speaking with parents and teachers about how the kids were doing.

Martin Demeter & Roma teamMartin Demeter with some of his players. Courtesy photo

“They did not always want to share this information with me, nor [did they] care what the kids did,” he admits. “That was a challenge.”

Recruitment began with players Demeter knew, then others heard about the team and joined. The district league, in which SK Roma Neratovice plays, welcomes kids ranging from seven to 19 years old.

The team is a year-round commitment for both the players and Demeter, who also works full-time for a Prague maintenance company. The team regularly goes swimming or running together to improve endurance. Some even play in a band together.

On top of managing recruitment and registrations, the coach organizes team fundraisers with his students, events ranging from soccer matches to carnivals. Students have volunteered to DJ, help with preparations, and even dress up as a clown to entertain other kids.

“This helps them feel like they are part of the team, since they’ve worked to raise their money,” says Demeter.

He emphasizes the effect the team has had on the community of Neratovice, where Demeter also grew up. More widely, playing against other Roma teams allows the players to meet more Roma students from other areas and cities, such as Ostrava in the Moravian part of the country, he adds.

“Often programs like this can motivate and inspire other kids in the community,” Pleskova agrees.

Turning a Blind Eye

SK Roma Neratovice also plays against non-Roma teams, and the players regularly encounter racism when playing, especially in different regions and when they win, Demeter says.

During matches the Roma kids regularly hear racist taunts and sometimes act on them, causing fights. “I try to talk to them about it and [about] overcoming the urge to react in a physical way,” Demeter says.

However, the kids get discouraged, are sometimes afraid to go to matches, and some have even quit because of the insults from other teams. “I talk to them and explain that, unfortunately, this is the way it is and they cannot take it personally,” Demeter says.

Team members also accuse referees of racism, saying they often let pass bigoted comments from opposing teams, or claim not to have heard them. This was one of the reasons Demeter decided to become a referee himself.

“I am now friends with many referees, and I’d say about half of all of them are racist,” he says.

The students experience racism at school and have told Demeter that they guess over 50 percent of those around them are racist.

“I think that is a bit of an exaggeration, but nevertheless that is how they feel,” he says.

A March 2018 survey by the Public Opinion Research Center found 37 percent of Czech respondents had a “very unfavorable” attitude toward the Roma population and 36 percent were “somewhat unfavorable.” The survey, which examined the attitude of Czechs towards 17 national/ethnic groups living in the Czech Republic, showed that the highest negative feelings were directed at the Roma people and Arabs.

Demeter has two daughters, Daniela, 12, and Martina, 9, who both say that when they grow up, they want to move to another country that is less biased against the Roma.

Demeter himself thinks that racism in the country is decreasing, as Czechs get used to minorities around them. “But it all starts at the family level and how parents are raising their kids to view others,” he adds.

He was recently asked to run for office by a political party member who also feels that racism is a problem in the country, but Demeter declined because he wouldn’t have enough time for the soccer team, which remains his first priority.

“I want to show them they are capable,” he says.

Melanie Ritchot is a student at Carleton University’s School of Journalism in Ottawa, Canada, with an interest in indigenous issues coverage and foreign affairs. She participated in TOL’s summer course for aspiring foreign correspondents, where she originally researched this story.

Education

Education